Logarithms and steel.

Remember logarithms? There was a time I used them constantly. If you think a logarithm is something an aborigine might bang out on a fallen tree, you're not getting my drift.

Umm. No.

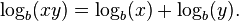

Logarithms were introduced by John Napier in the early 17th century as a means to simplify calculations. They were rapidly adopted by scientists, engineers, and others to perform computations more easily and rapidly, using slide rules and logarithm tables. These devices rely on the fact—important in its own right—that the logarithm of a product is the sum of the logarithms of the factors:

Forget all that.

I suppose mathematicians still use them somewhere, but back in the days before portable computers and scientific calculators, logarithms were a necessary tool.

When I started as a draftsman just out of college there were no handy electronic calculators of desktop computers. No one had even conceived of a laptop computer. Mainframe computers were around, actually, but mostly in large businesses. It would be ten years or so before Alamo Steel, the company I worked for, would have access to a mainframe for accounting.

I was a draftsman, fresh out of college. My math skills were, umm, a bit shaky. Sure, I was okay with basic math, and I had geometry licked. In high school I basically taught my geometry class. The math teacher used to duck out of class for a cigarette in the duplicator room after telling me to explain the homework to the rest of the class. I'd had trigonometry in college, although I'm afraid little of it stuck.

I finally learned, though. When I started working on hip and valley beams and stairs and handrails I was using trig constantly.

This means doing higher math while juggling feet, inches and sixteenths of an inch!

Sure , you can convert to decimals to calculate some things, but ultimately you have to convert back since the required outcome of the procedure was to produce drawings for our shop employees to fabricate steel members with. Our shop guys were great guys, I was friends with many, but quite a few barely spoke English, others could not read. They learned to use a steel tape measure, but it was considered a bit much to subject them to more than the most simple measurements to work with.

So, we in the drafting room were called upon to simplify, and especially to do all of the math and conversions in advance.

One of the first calculating tools I worked with was a slide rule.

This was, by the way, toward the very end of the heyday of the slide rule. Slide rules use logarithms. The beauty of logarithms is to simplify calculations. When you have multiplication, division, and other complicated operations to perform, you only have to use a conversion table to change the factors to their logarithms, then all operations become addition and subtraction problems.

We all learned multiplication tables in school. Those work great for simple whole numbers. If you are working with complex numbers of many decimal places it can be tedious to sit there and multiply or divide the whole thing out the long way. For instance, if you are multiplying two numbers, you use the tables to convert them to their logarithms, add the two logarithms together, then convert the logarithm sum back to real numbers. That's your answer.

Remember, electronic calculators were not available!

A slide rule, or slip stick, manually added and subtracted logarithms. The scale was a logarithmic scale. If you lined it up to multiply two and two, the answer was four. What it was doing was adding the logarithms for the two numbers graphically, and letting you read the answer.

For a while slide rules, well, ruled! A skilled engineer could read one to several decimal places, and do complicated problems all day long.

Other sorts of slide rules appeared. Not really technically slide rules, as they didn't use logarithms as such, but they did match up factors to show pre-calculated answers. They were common for many fields that required quick and practical calculations. My chosen field before drafting was electronics. I made use of, and still own, several cardboard cutout calculators that were this sort of slide rule. Very practical and quick to use. I still use them from time to time.

| |

| Ohmite Capacitor Calculator |

Once in awhile one of the hobbyist magazines would even print a similar one to copy, fold and tape together.

Did I mention useful?

Anyway:

Eventually my original K&E slide rule, or slip stick, got replaced.

For simple adding and subtracting of measurements, we did have electrical adding machines with special keyboards and a paper tape readout.

| |

| Monroe Foot-Inch-Sixteenth Machine |

|

| Victor Foot-Inch-Sixteenth Machine |

These were great. Some of us even used mechanical adding devices, known as Addiators, that used a metal stylus. You used the stylus to advance numbers in one direction for adding, the opposite direction for subtracting. With many of them you kept track of sixteenths of an inch manually, literally, by holding up a pinky finger when you had a sixteenth in the number, folding it away when you didn't. A very few of the Addiator models actually handled sixteenths of an inch.

| |

| Addiator |

No electricity, but so much more portable! That was important for those of us who, shall we say, labored with side jobs in the same industry?

The engineers in the company often used a specialized adding machine that allowed you to reset the decimal point, to more rapidly work with big numbers. It did require the conversions to be made from feet and inches to decimals, but once those conversions were made, their calculations could be carried out and the answers converted back at the end.

|

| Shifty Monroe Machine |

You actually manually moved the carriage over to the correct decimal place column. Some of these had a little crank below the keyboard to do this! Sure, it was electric, but still, can you say Fred Flintstone?

An integral part of the calculating process was a book. Several of our available books did have the foot-inch-sixteenth to decimals of a foot conversions available, but one book was our math “bible”.

|

| Smoley's |

Smoley's Tables were available either as four separate books, or all four combined into one volume. The fourth volume, Segmental Functions, was useful for circular calculations, critical when needed, but rarely used. The first three volumes had to do with decimal equivalents, squares, logarithms, and trigonometric functions. Those we used constantly. We were each required to obtain our own Smoley's books. When we could, we got the first three together in one volume, and the fourth separately. That fourth Segmental Functions volume would last forever, and did! We could often wear out two or three of the first three volumes before the fourth would even show wear.

Those logarithms and trig functions really came in handy! Perhaps I should also mention that this was in the days of manual drafting as well. Lead pencils, T-squares, triangles, lettering guides, drafting tape, tracing paper. CAD programs did not exist. Dinosaur days. This was in 1971 and years following.

We had to know the mechanics of drawing a pencil line, and construct various shapes to put together a useful drawing, and then to hand print the lettering to explain and dimension everything. Then, copies were made with a smelly ammonia Ozalid process to produce real “blueprints”.

We ended each day with liberal amounts of graphite and rubber eraser dust on ourselves.

|

| TI Calculator |

Well, after a few years, Texas Instruments came along with a series of hand held electronic calculators. Now THAT was revolutionary! We still had the conversion problem to deal with, but suddenly it was less of a chore. The so-called “scientific calculators” appeared with more and more functions, including trigonometric functions that made things easier. We were able to rely less and less on the Smoley's tables, and go straight to calculating.

|

| Bigger than a breadbox Wang |

About the time that mainframe computers became more accessible and user friendly, programmable calculators appeared. The first were pretty large affairs. The Wang programmable was one we utilized for awhile. Pretty nifty! I actually taught myself to write programs for it! (As a mere draftsman, this was a bit above my station, but I tended to color outside my lines a lot!) Two number pads with memories meant you could perform more than one operation at a time and merge the answers. Also, it sported a cassette tape program storage, so you could record and reload several programs as you needed them! Display screens were still in the future, all usable output was preserved on paper tape printout.

After only a couple of years, those same hand held calculators we were using became programmable as well. First one, then many programs could be stored and used. The Wang was fairly obsolete in no time. It still worked well for some situations, but for everyday calculations the hand helds were the thing.

It was not until the mid '80's that we were able to finally ignore that conversion problem. Development of calculators that actually worked with fractions and inches was ignored until then. The United States was considering going metric for many years but there was a lot of resistance. Most of us dinosaurs didn't really want to learn a new system.

The manufacturers finally gave in and designed a few calculators that actually worked in feet-inches-sixteenths. This is the one I have now. It has taken the place of every machine/calculator/book that came before. This is the Jobber 6 by Calculated Industries. It's great! Online versions are even available, so you can use it without taking your hands off the computer keyboard.

That's important, since Computer Aided Drafting also took over from manual drafting. Of course, most of the major CAD programs like Autocad have several calculating functions built right into them, but... remember those aforementioned dinosaurs?

I still have my board and pencils, too. I might even have my copy of Smoley's around somewhere!

I admit I've gotten a bit rusty on interpolating logarithm tables. On the other hand, it's been awhile since I've detailed steel as well. Still drafting, though, with CAD and my Jobber!

No comments:

Post a Comment